There are almost as many translations of the Bible available today as there are denominations of Christianity to choose from. They range from reformulations of the KJV 1611 to a version which has completely removed any masculine personal pronoun for God. The overflow of Biblical translations may leave believers, whether they are new believers or old ones, at a loss as to which one to choose.

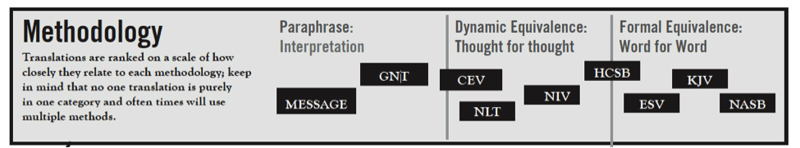

My hope is to help you understand not just how translations are categorized, but what you should personally be looking for in a translation to stick with and why I’ve chosen the one I’ve settled on. Essentially, translation teams take one of two approaches when converting the Hebrew (Old Testament) and Greek (New Testament) texts to English: some strictly translate the Scripture word-for-word from the original texts, which is a process called formal equivalence. Formal equivalence also preserves the grammar of the preserved Scripture texts. Others translate a thought or concept, rather than individual words, employing instead an approach called dynamic equivalence.

Recently though, a third approach to language translation has emerged, called the paraphrase. At its most basic, a paraphrase is a version in which the translator (or author) expresses the Scripture in his own words. The Message and the Living Bible are popular paraphrases. While paraphrases can be helpful or inspirational, it is best to read them alongside an actual translation of God’s Word, as a paraphrase is, by nature, not wholly accurate to the source text.

Many people prefer dynamic equivalents, such as the New International Version (NIV) or New Living Translation (NLT), because they feel they are easier to read and understand. However, these versions are more subjective than formal equivalent translations, because they require the translators to inject their own understanding of Scripture into the text. This is not to say that these versions are untrustworthy, nor is it to say that they should be avoided, merely that more unbiased translations are widely available.

For Bible reading and study, I recommend that you choose a translation as close as possible to the original languages, for you will receive words in English as near to the words given by God to the original authors of Scripture as we can get without learning New Testament Greek. God has not only imparted His divine, eternal truth to us in the hearts of the statements in Scripture, but also in the words themselves. The more you study God’s Word, the more your desire will be to know the exact word used in the particular passage you are reading.

My Decision

After much reluctance, I finally settled on using the Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB) during my quiet time for the past few months. I was made aware of the HCSB during my seminary days but didn’t give it much attention because of my commitment to the English Standard Version (ESV). My love of the ESV started in 2005 after two previous relationships with the New International Version (NIV) and the New American Standard Bible (NASB). Both, in their own right, were good translations, but the ESV surpassed them for its approach of formal equivalence.

Before the ESV, I had switched from the NIV to the NASB because I found myself wondering what the more exact meaning of the Greek and Hebrew words were as I studied. After months of studying with two Bible translations opened side by side, I realized how substantial the differences between the two were and converted to the NASB because of its attention to detail in this area.

However, even the NASB was lacking in a few ways. For example, the NIV was written on a 7th grade reading level, as opposed to the NASB’s 11th grade reading level. What does this mean to the reader? It was great for serious study, but not so great for reading. Furthermore, memorization was difficult because the translation didn’t flow as smoothly as a dynamically equivalent rendering.

So when I discovered the ESV, it was as if I struck Biblical gold. Combing both the word-for-word accuracy of a literal translation and the poetic beauty of a dynamically equivalent version, the ESV was the best of both worlds for me. For almost a decade, I have read, memorized, and meditated on the ESV, enjoying the richness of the theological flavor mixed with a modern attractiveness. So why would I leave the translation I love so much?

Let me offer 7 reasons that convinced me to consider the HCSB over the very familiar and usable ESV:

1. It’s a Translation from the Original Language, not a Revision of a Former Translation.

The ESV is a revision of the RSV (Revised Standard Version), which was updated years ago as the NRSV (New Revised Standard Version). Even the original 1611 King James Version was a revision of the Bishop’s Bible. It then went through multiple translations over the next 150 years until the 1769 Oxford Blayney translation, the one in use today, which contains 25,000 variations from the 1611 version, along with 1500 significant changes.

Furthermore, translations prior to 1991 are limited in scope in regards to comparison with the Qumran discovery in 1947-1956. Translators did not have access to the Dead Sea Scroll fragments since they were not made widely available until that time. What is so refreshing about the HCSB is that, unlike even many well-loved versions, it doesn’t allow tradition to influence the translation.

For example, let's examine John 3:16 in several translations:

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life. ESV For God so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life. NASB

The word “so” in the sentence is the word I want us to consider. The ESV and NASB cause the reader to think that “so” refers to an extent, such as “I love Kandi (my wife) so much.” But in its original context, the word “so” in John 3:16 carries the idea of expression or demonstration. It emphasizes the way God loves the world, which is why the translators chose to render the verse as such: For God loved the world in this way:

He gave His One and Only Son, so that everyone who believes in Him will not perish but have eternal life. HCSB

2. It Uses the Personal Name of God

Many translations distinguish God’s name “Yahweh” from his title “Lord” by capitalizing the word LORD in the Old Testament. This can be quite confusing. Yahweh is not a title. It’s God’s personal name.

Isaiah 42:8

NIV: I am the Lord; that is my name! I will not give my glory to another or my praise to idols.

ESV: I am the Lord; that is my name; my glory I give to no other, nor my praise to carved idols.

HCSB: I am Yahweh, that is My name; I will not give My glory to another, or my praise to idols.

3. “Messiah” is Used in Place of “Christ”

No one calls me Robby Pastor at my church. Why? Well, because Pastor is a title describing what I do. Robby is my name. The word, “Christ” is not Jesus’ last name, rather it is the Greek word “Christos” which means “Messiah” or “Anointed One.” It is a title describing who Jesus is and what he came to do (e.g., the Messiah came to redeem Israel as promised in the Old Testament). The HCSB extenuates the Hebraic concept of “Anointed One” by using the word “Messiah.”

Isaiah 42:8

NIV: The people were waiting expectantly and were all wondering in their hearts if John might possible be the Christ.

ESV: As the people were in expectation, and all were questioning in their hearts concerning John, whether he might be the Christ...

HCSB: Now the people were waiting expectantly, and all of them were debating in their minds whether John might be the Messiah.

4. It Removes Archaic Words

Most translations include archaic words like behold and shall, terms that have been preserved through the ages. Unfortunately, we don’t use them anymore. When was the last time you said, “Behold, a beautiful sunset”? Words such as shall or behold are eliminated and replaced with familiar words like look.

| KJV | ESV | NIV | NLT | HCSB | |

| "Behold" | 1326 | 1106 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| "Shall" | 9838 | 6389 | 467 | 8 | 0 |

Another example is the word blessed (or bless-ed depending on where you are from and in what context it’s used). In some contexts, the word happy is a better rendering, as seen below in Psalm 1:1. Another textual variation worth noting in Psalm 1:1 is the rendering of “standing in the way.” In both the ESV and NIV, “Standing” conveys the idea of something obstructing a path, but in Psalm 1, it means, “to follow the path of someone.” Therefore, the HCSB captures the intended meaning of the text by stating, “take the path of sinners.”

Blessed is the man who walks not in the counsel of the wicked, nor stands in the way of sinners, nor sits in the seat of scoffers; ESV Blessed is the one who does not walk in step with the wicked or stand in the way that sinners take or sit in the company of mockers, NIV How happy is the man who does not follow the advice of the wicked or take the path of sinners or join a group of mockers! HCSB

5. The Use of the Word “Slave” in Place of “Servant”

The words “slave” and “servant” have very diverse meanings. A servant had privileges and rights separate and apart from his or her master. A slave, on the other hand, had no rights at all. The master provided everything they needed to live and required utmost respect and allegiance to them. A slave was a servant, but all servants were not necessarily slaves. The HCSB chose to use “slave” instead of servant to describe a believer’s relationship to Jesus. Here are a few examples:

Matthew 10:24, “A disciple is not above his teacher, or a slave above his master.”

Philippians 1:1, “Paul and Timothy, slaves of Christ Jesus: To all the saints in Christ Jesus who are in Philippi, including the overseers and deacons.” 2 Corinthians 4:5, “For we are not proclaiming ourselves but Jesus Christ as Lord, and ourselves as your slaves because of Jesus.”

6. It’s not just a Baptist Translation

For years, I naively discounted the integrity and veracity of the HCSB translation team out of ignorance. Contrary to my previous belief, the team consisted of more than just Baptist theologians. The 100 member cross-denominational team was comprised of a total of 17 Protestant denominations. Translators used the most reliable, current editions of both the original Greek and Hebrew manuscripts to create their new translation:

- Nestle-Aland’s Novum Testamentum, 27th Edition

- United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament, 4th Edition

- Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, 5th Edition

7. Old Testament Scriptures are in Bold Letters

When an Old Testament Scripture is quoted in the New Testament, the words appear in bold letters. Let me offer two examples of familiar passages:

Romans 3:10, “As it is written: There is no one righteous, not even one. 11 There is no one who understands; there is no one who seeks God. 12 All have turned away; all alike have become useless. There is no one who does what is good, not even one.”

Romans 10:11-13, “11 Now the Scripture says, Everyone who believes on Him will not be put to shame, 12 for there is no distinction between Jew and Greek, since the same Lord of all is rich to all who call on Him. 13 For everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.”

Ultimately, there is no perfect translation. Even if you are fluent in Greek and Hebrew, you still have to interpret the text in some form or fashion when you convert it from the original language to our language. When it comes down to it, the best translation is the one that gets read. Unfortunately, many who argue for a particular translation over another may never read the one they are proposing.

The translation that you will faithfully read and study is the best translation for you. For me, for now, I will continue reading and preaching from the HCSB.

Let me offer you a challenge: Read the HCSB for the next month before formulating an opinion. I read it devotionally for 3 months before I was persuaded. Let me know your thoughts.